Driving Around

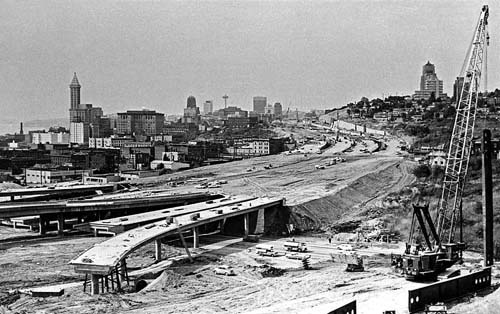

On January 31, 1967, the last section of Interstate 5 from Everett to Tacoma was completed after more than a decade of planning and construction, mixed in with sizeable portions of squabbling, second-guessing, and setbacks. Two years later, the final segment of I-5 – including 11 bridges – was completed between Marysville and Everett, allowing for smooth, uninterrupted travel from the Canadian border to the northern California state line. At least for the time being.

Plans for a "toll superhighway" connecting Everett, Seattle, and Tacoma were first drawn up in 1953, but three years later the Washington State Supreme Court declared the toll-road idea unconstitutional. Around the same time, the federal Defense Highways Act became law, which helped resolve the dilemma. By the end of 1957, the state highway board had chosen a route and secured federal funding.

Not everyone was happy. The new route gouged through much of Seattle – including downtown – and some Seattleites voiced their concerns at protests and public meetings. Victor Steinbrueck, who would later lead the movement to save Seattle's Pike Place Market, argued that the city would lose some of its historic buildings through demolition. Architect Paul Thiry advocated a lid for the downtown portion for aesthetic reasons, and Seattle Mayor Gordon Clinton stressed the need to put light rail in between the highway lanes. Many of these suggestions fell by the wayside in the name of progress.

But after the highway opened, traveling north and south through Seattle became a breeze – partially because fewer people were then commuting. By the end of the century, the economy was booming, and motorists had become used to the giant gash coursing through their city. Since then, traffic has greatly increased, causing major slowdowns throughout the Everett-Seattle-Tacoma corridor. Mass transit has helped to ameliorate the problem somewhat, but the combined issues of geography, growth, and costs factor into a transportation quandary that has not been easy to solve.

Under the Ground

Prior to I-5, SR-99 was the main thoroughfare through Seattle, and when the first section of the Alaskan Way Viaduct opened in 1953, it offered a limited-access route that removed highway traffic from city streets. Thousands attended a ribbon-cutting celebration, which included a parade of vintage cars that were as old as the dreams of the viaduct itself. Seattle had been considering a downtown bypass as early as the 1910s.

Planning and design of a waterfront viaduct involved a strengthened seawall, which wasn't completed until the 1930s. Funding for the roadway itself took another 10 years, and construction didn't begin until 1950. The final phase of the project was completed in 1959, and in 1966 the last piece put into place was the sole on-ramp from central downtown. Other connections were planned but never implemented, partly due to a shift in emphasis to Interstate 5, then being completed.

Since its opening, the viaduct had its critics, many of whom felt that the elevated roadway had a negative impact on the city's central waterfront. The debate raged for years, but with no viable alternative for shifting traffic to a different route. It wasn't until the 2001 Nisqually Quake damaged the aging viaduct's joints and struts that serious consideration was given to either removing, rebuilding, or redesigning the roadway.

After a decade of extensive debate, replacement of the viaduct with a deep-bore tunnel garnered enough support, and the first phase of demolition of the southern end of the viaduct began in 2011. Construction of the tunnel began in 2013, and after some initial problems with the tunnel-boring machine, the pathway was completed in 2017. Six years ago this week, the new State Route 99 Tunnel opened to traffic on February 4, 2019.